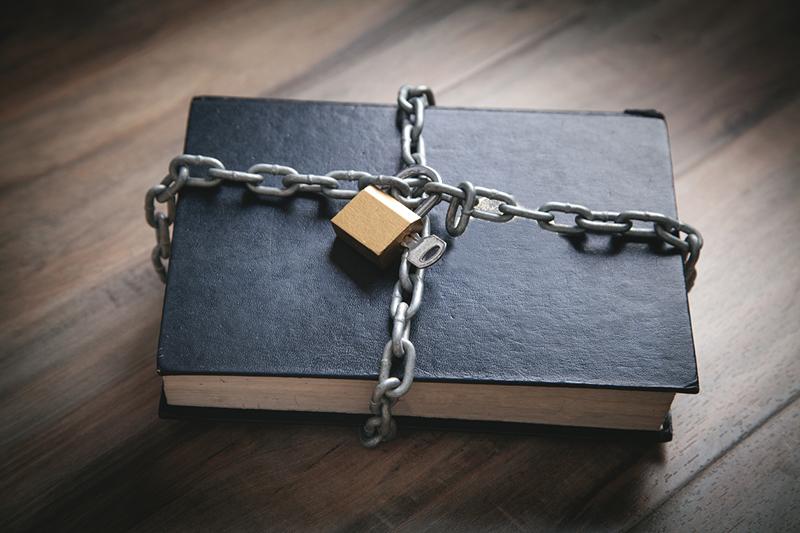

The nationalist focus of Project 2025, the policy wish list that has inspired the recent codification of book bans and classroom censorship within the US, means that it may be easy to assume that global higher education structures are immune from similar attacks on intellectual freedom. Yet, we have already seen that book ban challenges are growing in UK school libraries with increasing numbers of primary- and secondary-school librarians being asked to remove particular titles from their shelves. More specifically, the central role that the US plays in scholarly communication means that Republican attempts to align research with state ideology is already impacting the work of academics around the world, including teaching, supervision and publishing.

Key threats include the weakening and elimination of academic research resources, which will make search more arduous while decimating access to certain materials, as well as the introduction of uncertainty into scholarly knowledge exchange structures, which will render PhD research and the dissemination of ideas far harder to achieve.

Fine-tune your approach to information literacy

One of the most visible implications of attempts to censor scholarly work is the upending of how scholars around the world navigate US-based information environments. Where research might once have been a mundane task, ideological actions mean that enquiry becomes more complex as resources are taken down and established search techniques become unreliable. Take access to academic research as an example. Executive orders aimed at eliminating diversity, equity and inclusion terminology from government websites and datasets mean that both the collection and the indexing policy of federally funded databases such as PubMed and Medline are under threat, while cuts to the US Department of Education saw ERIC (Education Resources Information Center), a database that supports research in the field of education, briefly shuttered in April. Primary sources face a similarly uncertain future, with environmental, health and atmospheric science data already removed from US government websites and references to the contributions of racially minoritised communities to social and military history deleted from the websites of the National Park Service and the Smithsonian, among other institutions.

- Protecting your work – and your values – in US higher education

- Boosting data literacy: essential skills for early career researchers

- A framework to teach library research skills

While ERIC has been granted a temporary reprieve, attacks on intellectual freedom will evidently only make it harder to access research, particularly for those who have become accustomed to one-click searching. Beyond creating increasingly dispersed scholarly ecosystems, the unreliability of federal sources will further decrease the visibility of grey literature given the prioritisation of major publishers within commercial search engines. Efforts are under way to recover some of the deleted data, thanks to librarians and other information workers. However, these archival projects are scattered and stymied by funding challenges of their own. The housing of global classification systems within US federal structures means that search, too, will become less reliable, as illustrated by proposals to eliminate references to Covid-19 from the cataloguing guidelines that are used by UK libraries.

Researchers will need to develop a raft of new techniques to adjust to censored information environments. These include becoming more deliberate about search strategies, as the list of words banned by federal agencies works to obscure the many ways in which human life is lived. It may also include working across a broader range of discrete search tools, including personal websites and repositories alongside library discovery systems, as underlying scholarly infrastructures become less robust. The compromising of information sources will also require librarians to ensure student information literacy sessions are designed to help newer researchers navigate research absences and silences rather than the more typical information overload.

Shore up mechanisms for knowledge exchange

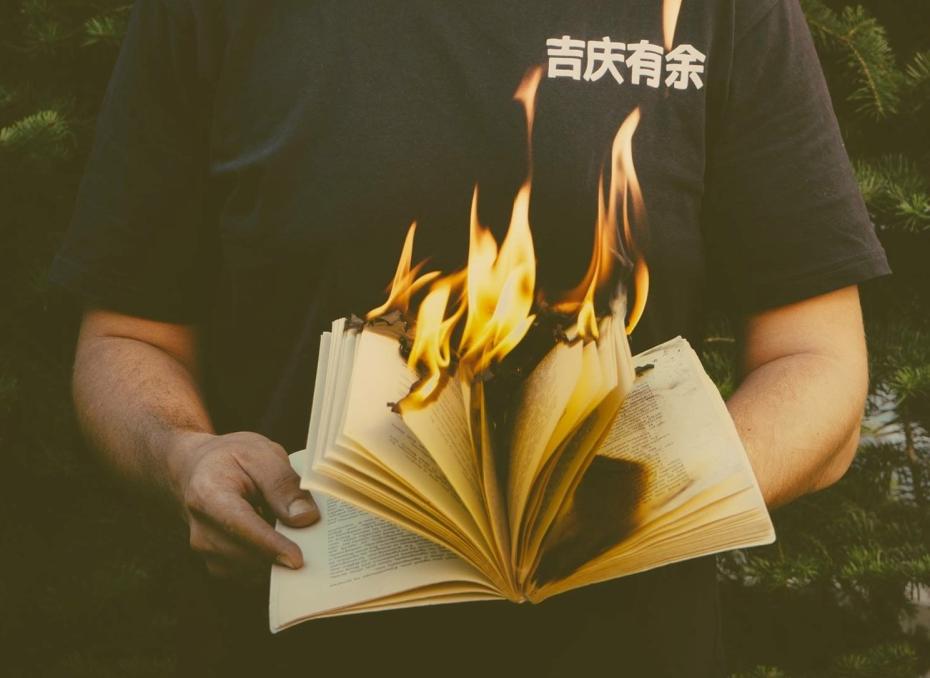

Another noticeable impact of attempts to control the dissemination of ideas is the weakening of the knowledge exchange structures upon which scholarship has typically relied. It remains to be seen, for example, how the publishing industry will react to systematic attacks on intellectual freedom and university DEI initiatives. Already, libraries in Mississippi are removing race relations and gender studies databases that they perceive to fall foul of new laws. If other libraries, schools and colleges follow suit by cancelling publishing contracts, editors may decide that it is not worth their time and energy (or the loss of political goodwill) to continue either commissioning or distributing certain forms of scholarly work.

Journals, too, are well within the administration’s cross hairs, with reports that various federal agencies have attempted to intimidate even independent serials into publishing more “alternative viewpoints”. Other scholarly endeavours that are thrown into disarray through the suppression of “inconvenient” materials include the work of PhD students and early-career researchers. Taisha Richards, for example, who is in her first year of studying the sexual abuse and exploitation of enslaved peoples in Louisiana, spoke movingly at an event organised by the University of Bristol’s American Studies Research Group about how attempts to control knowledge might affect her work, including the availability of primary sources and fieldwork opportunities.

Researchers will need to remain vigilant to what may be rendered impossible if attacks on scholarly endeavours continue. Supervisors should check in with graduate students about the feasibility of their project if primary sources or travel is in jeopardy while further offering support for work that might need to be creatively reimagined given constraints. Richards further recommends working with archivists to assess whether the digitisation of records that are most at risk of being suppressed through state interference might be prioritised. Researchers on editorial boards should additionally adopt the Council on Publishing Ethics (COPE)’s guidelines related to handling banned terms, as well as editorial independence and censorship challenges, while further shoring up digital archiving arrangements.

Moving forward

The substantial challenges that authoritarian ideology poses to knowledge exchange mean that researchers must be prepared to safeguard their commitment to empirical insight. Yet, resistance to censorship cannot merely devolve into a defence of the status quo, as so often happens with crisis narratives. The work of librarians and archivists has been key in challenging the cost and labour inequities of academic ecosystems, and this work must continue alongside the new focus on intellectual freedom. We should prioritise this work in the coming months as the Trump administration continues its campaign to bring the world’s informational infrastructures further under its control.

Alison Hicks is associate professor of library and information studies at UCL and editor of the Journal of Information Literacy.

If you’d like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment