Graduate apprenticeships are transforming Scotland’s higher education landscape, with tens of thousands of learners now earning degrees while working. However, our research has revealed a critical insight that policymakers and employers are overlooking: the paradoxical nature of apprentice autonomy.

The freedom-confidence contradiction

Our study of 50 apprentices across two Scottish universities uncovered a striking contradiction that challenges conventional approaches to work-based learning. While 61.5 per cent of apprentices report having “significant” or “complete” autonomy in their workplace learning, the correlation between their perceived autonomy and their ability to use that independence effectively is virtually zero (r = 0.106). We measured this through surveys assessing how well apprentices could manage workplace projects, direct their own learning and apply their skills in practice.

- Graduate apprenticeships need link tutors – but who’s looking after them?

- Higher apprenticeships reimagined for lifelong learners

- Are we overlooking the power of autonomy when it comes to motivating students?

This “autonomy paradox” challenges the assumption that simply providing independence is enough for developing workplace talent. The reality is far more nuanced – discretionary learning, defined by enhanced employee autonomy and creative problem-solving, requires sophisticated support structures to be effective.

When autonomy meets vulnerability

The autonomy paradox is particularly pronounced for graduate apprentices, who face different kinds of pressure from traditional undergraduates. Unlike campus-based students, apprentices must simultaneously balance full-time employment, academic coursework and often family obligations – a complex juggling act that can lead to isolation and stress.

Apprentices with high autonomy don’t automatically achieve better learning outcomes, according to our research. Learning outcomes by autonomy level show only modest differences: low autonomy (47 per cent), moderate autonomy (53 per cent) and high autonomy (62 per cent). The gap is much smaller than expected, suggesting that autonomy alone is insufficient for success.

The university support revolution

Perhaps our most surprising finding overturns conventional wisdom about who drives work-based learning success. The research reveals an exceptionally strong positive correlation between university support and effective autonomy (r = 0.765), while employer support shows a negative correlation with learning outcomes during the programme (r = –0.233).

This suggests that universities, not employers, are the key to making workplace autonomy effective. Workplace demands can actually interfere with learning during the programme, making academic support structures even more critical for apprentice success.

The tri-sphere model: a developmental framework

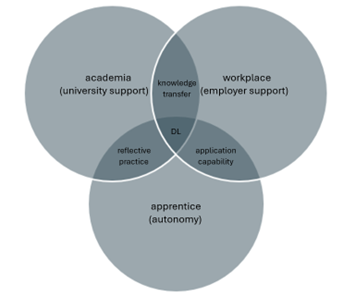

To understand how discretionary learning operates in graduate apprenticeships, our research developed the tri-sphere model. It visualises effective work-based education occurring at the intersection of three key domains: academia, workplace and apprentice agency.

Crucially, our findings reveal that optimal learning combinations change dramatically over time:

Current students: “Academia + apprentice” achieves 71.9 per cent effectiveness. Academic theory combined with individual reflection creates the optimal learning foundation, while workplace integration can wait until core skills develop.

Alumni: “All three domains” reaches 94.6 per cent effectiveness. Full integration becomes optimal once foundations are built, representing a dramatic shift in what works over time.

The most striking transformation occurs in “academia + workplace” combinations: current students achieve 0 per cent effectiveness. In contrast, alumni reach 81.2 per cent effectiveness – an improvement of over 81 percentage points. This suggests that attempting to integrate academic learning with workplace demands too early may actually impede development.

The hidden heroes: academic link tutors

Central to successful integration are academic link tutors. We found them to be critical success factors in our research. They bridge the vital connection between university learning and workplace application, helping apprentices translate theoretical knowledge into practical skills, while also providing crucial pastoral support.

The statistical evidence for university support’s importance validates the critical role these tutors play. As graduate apprenticeship programmes expand across Scotland, ensuring these tutors receive proper training, resources and institutional recognition becomes fundamental to maintaining high-quality learning environments, where discretionary learning can flourish.

Exceptional long-term impact

Our research reveals one of the strongest correlations documented in apprenticeship research: the relationship between graduate apprenticeship impact and ongoing learning capabilities (r = 0.871). This finding is supported by remarkable long-term outcomes:

- Learning effectiveness improves from 57 per cent (current students) to 86 per cent (alumni)

- 100 per cent alumni retention rate in the region

- Self-reinforcing learning cycles that continue long after graduation.

This evidence suggests that graduate apprenticeships create lasting regional innovation capacity rather than just individual skill development.

Collaborative innovation over individual brilliance

Contrary to popular assumptions about entrepreneurial talent, successful workplace autonomy is built on collaboration, rather than individual capabilities, according to our research. Among alumni, team development shows the strongest correlation with autonomy effectiveness (r = 0.608), significantly outperforming individual innovation measures (r = 0.279).

This finding suggests that, rather than being lone innovators, effective apprentices develop the skills to cross boundaries and help organisations integrate different types of knowledge and capability.

Investment that transforms regions

For employers concerned about return on investment, the research offers compelling evidence that graduate apprenticeships create virtuous cycles benefiting both individuals and organisations. Alumni consistently rated knowledge sharing (90 per cent) and process improvement (87 per cent) as their strongest workplace contributions.

More importantly for businesses focused on talent retention during skills shortages, the 100 per cent regional retention rate demonstrates that well-supported autonomy creates stronger organisational commitment, rather than encouraging talent migration.

Evidence-based recommendations

Based on our research, we suggest these actions:

- Recognise that your support systems are more critical than employer support for apprentice success

- Create formal structures for three-way communication

- Invest in academic link tutor capabilities as strategic priorities.

As Scotland positions skills development as a cornerstone of future prosperity, understanding the autonomy paradox becomes increasingly important. Graduate apprenticeships represent a critical mechanism for addressing skills shortages, but their success depends on sophisticated understanding of how discretionary learning develops.

Meaningful workplace learning happens not through independence alone, but through independence properly supported by university structures that evolve over time, as our research shows. For a nation investing heavily in developing a skilled workforce, the message is clear: the future of graduate apprenticeships lies in recognising their developmental nature and investing accordingly.

Elaine Jackson is a lecturer in business and management and Alan MacDonald is a lecturer in work-based learning, both at the University of the West of Scotland.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment