As we progress through 2025, turbulent politics, ongoing conflicts, and global and domestic challenges flood our news feeds and algorithms. This is without even considering the precarious state of the UK university sector itself.

So, it is understandable that students and staff within higher education may be experiencing heightened concerns. While each individual’s response will vary, a sense of unease appears to be common. This article explores strategies to help students and staff to focus on what we can control, rather than what we can’t, and navigate uncertainty.

How the concept of control affects emotional well-being

As human beings, we find comfort in certainty, fixedness and the known. When under threat or duress, we seek out the safety of routine, repetition and the familiar as part of our internal security system. The tricky thing is that we live in an ever-changing world which, to say it bluntly, doesn’t give a damn about our needs and carries on changing regardless.

- Spotlight guide: Make good mental health a university priority

- Teaching the unknown: how to prepare students for uncertainty

- Resource collection: Well-being in higher education

However, adaptable creatures that we are, we have become attuned to seeking control. We seek to create a routine and establish a “safe haven” against the bitter winds outside. What complicates our endeavour is how big our worlds have become. With the capacity to connect and access information globally and instantaneously, suddenly it feels as if a lot more needs to be “controlled”; we have far more to possibly feel safe from. Herein lies the issue…the notion that we, a self-aware species, should be able to control everything.

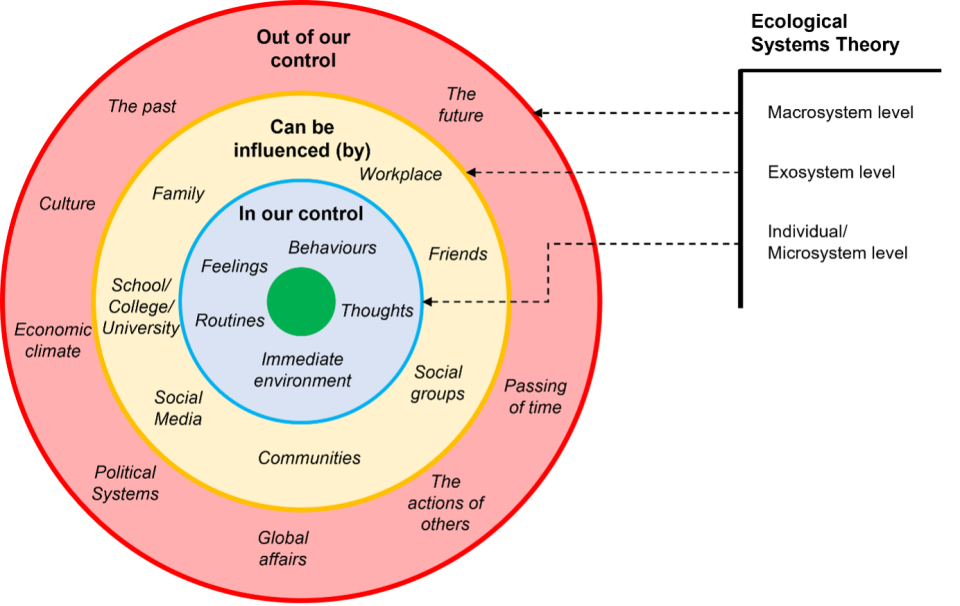

Our focus on control can be aptly demonstrated through the three circles of control model. This exercise seeks to organise our attention into concentric circles: what is in our control, what we can influence, and what is not in our control. The distance from the centre represents our decreasing hold over decisions and events (see image below).

Injecting concepts of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory of how our beliefs and development are shaped by our wider social and societal circles, we begin to see the varying influence that these have on an individual but also the diminishing degree of control/influence the individual can reciprocally exhibit as we expand further out into larger ecological systems.

So, how do we hope to capture that inner safety we fervently seek? A simple change of focus.

Take a moment, let our focus retreat from the outer circle and come closer to our centre. Let it reside in the inner circle of what is in our control right now. Consider what this may include – our thoughts, emotions, behaviours and our immediate environment. Possibly our day-to-day activities, our self-care routines and our life duties. Does it involve engaging in mindfulness or creating healthy boundaries with our social media consumption?

Now, let’s explore our values. If we feel so passionately about the injustice and unfairness in the world, is there anything we can do right now about this? If we find that the answer is no, try smaller. Look to the simplest of affairs that we may have missed, such as simply reading an article on reframing our approach to control (shameful plug).

Imagine our bubble expanding to sit now in the middle circle of what we can influence. What might we find within? Do we feel able to positively influence change in others around us, our friends and family? Are we in a position to go further and influence our workplace or our communities? What steps can we take towards our values within this middle circle?

It is not to say that being aware and mindful of our outer circles is not helpful, as it often can reflect what is important to us. However, to excessively dwell there is to make ourselves more vulnerable to worries and concerns beyond our capacity to intervene. Instead, for the profit of our well-being, we must come to accept what is outside our scope of influence.

Our influence within a university context

On that note, and to conclude with practical advice, here are tips to help both you and your students feel more in control within the university setting.

- Signpost to well-being services: If you notice a student struggling (perhaps they’ve become withdrawn, missed sessions or disclosed personal difficulties), it can be empowering to know where to refer them. Whether it’s to counselling, mental health support or academic advisers, pointing students towards help can be a vital first step.

- Connect with staff networks: Many institutions host networks focused on shared identities or experiences, such as disability, LGBTQ+ or working parents’ networks. These spaces can offer solidarity, a chance to raise concerns, and peer-led support in challenging times.

- Engage with events and workshops: Attending sessions on social justice, student voice or well-being equips us with language, confidence and understanding to better support others, and ourselves, in conversations about difficult topics.

- Influence local change: Whether through committees, student partnership projects or offering feedback to your faculty, contributing to small changes can help reframe your role as one of influence, rather than helplessness.

- Model healthy behaviours: Maintaining professional boundaries, taking leave when needed, and talking openly about well-being can quietly challenge toxic norms and set a tone of compassion and sustainability for colleagues and students alike.

Imogen Varle is a mental health intervention officer at De Montfort University, and author and writer at HNDL magazine. Jay Cotton is an integrative counsellor/psychotherapist and well-being officer, also at De Montfort University.

If you’d like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment1

(No subject)