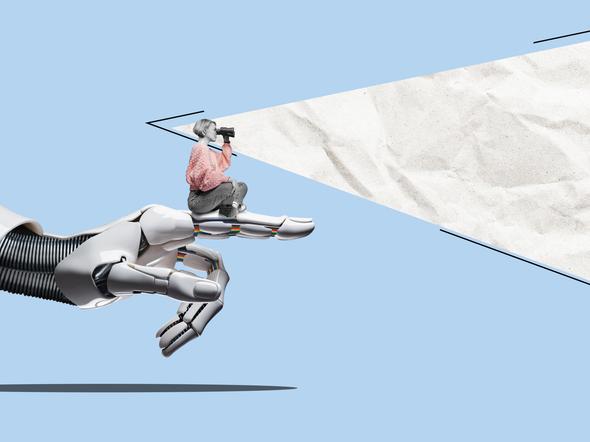

Educators tend to agree that we need to embrace AI as a tool for learning. However, there is still an open question about how academics and students can best harness the technology in the classroom.

Through our use of AI to enhance the classroom and online experience at our institution, we have developed best-practice guidance to ensure it complements our learning offer rather than detract from or homogenise it.

Public platforms

First and foremost, we need to accept that a significant proportion of students will use publicly available generative AI platforms such as ChatGPT and DeepSeek. The key here is to encourage students to use the platforms to enhance, rather than create written work – for example, using it for proofreading or to inspire ideas that help them broaden their understanding of the subject matter.

- An insider’s guide to how students use GenAI tools

- Keep calm and carry on: ChatGPT doesn’t change a thing for academic integrity

- GenAI can help literature students think more critically

Similarly, students should be encouraged to scrutinise what AI platforms tell them, using them to hone critical thinking and flesh out arguments rather than just taking the content at face value. This is important, as AI content can still be generic and lack depth, and students studying for a master’s-level course already know at least as much as ChatGPT about their subject.

Bespoke models

Bespoke AI chatbots are a useful option – offering students the opportunity to ask questions and receive instant responses that are tailored specifically to their course content. However, as research from our IDEA Lab found, students have a preference for face-to-face interaction. We need to reassure students that they can still contact their lecturers and request individual support as usual.

Taking chatbots a step further, we are developing tailor-made, course-specific AI avatar lecturers that can provide specialist, in-depth knowledge. These avatars appear as highly realistic video representations of the lecturer (as if you were on a live video call with them) and are trained to respond just as the lecturer would, using the same voice, mannerisms and, crucially, the same course content and supporting materials.

One of the most frequently raised issues with this type of technology is the risk of the output feeling distant, clinical or impersonal, especially when students are already navigating a digital learning environment. This means it’s important to make AI avatars feel as warm, familiar and human as possible. It can take months of iteration, testing and refinement to achieve the right tone, look and feel, from naturalistic voice inflections and body language to a friendly visual presence that mirrors the real lecturer.

And this is not the only careful step needed to secure student buy-in for the increasing use of AI technology. As the research from the IDEA Lab found, students care about AI content being accurate and in alignment with the lecturer’s input. They want to see content reviewed by staff, and they strongly feel that AI should complement, not replace, human interaction.

To achieve this, lecturers also need to be closely engaged in the development process, personally shaping the avatar’s content and verifying its accuracy. If they get this right, the technology can offer an additional layer of personalised, on-demand help that complements existing channels, to make support more accessible, responsive and tailored, without losing the human touch.

To further improve this technology, it can help for lecturers to receive anonymised reports of the questions students are asking their AI avatars. This not only helps fine-tune the avatar’s performance but also gives valuable insight into how students are engaging with course materials. This information, which is harder to capture through traditional channels, can allow us to adapt and improve teaching in real time.

Into the future

So far, the student response to these uses of AI has been positive. Our research shows that two-thirds of students find the idea of AI avatar lecturers appealing, with almost 60 per cent saying they would use them for additional support and just over half feeling that they could help explain complex ideas.

Faculty members have also responded positively. They appreciate the opportunity to enhance learning while providing support to students more efficiently. By addressing common queries and clarifying core concepts through the avatars, lecturers are able to focus their time on more advanced, high-value interaction.

How universities use this technology should be shaped by how students engage with it. The aim should be to stay responsive to their needs. Over time, we hope students will increasingly use AI to deepen their understanding of key concepts, enabling them to come into class better prepared for richer, more in-depth discussions.

As AI technology advances, we may be able to gamify learning experiences or create immersive simulations, such as virtual negotiations, crisis response drills or marketing pitches. These would allow students to practise critical soft skills such as leadership, persuasion and decision-making in realistic environments, providing dynamic, lifelike training grounds for complex, cross-functional problem-solving.

Ultimately, AI tools can open the door to a more responsive, practical, skills-based approach to learning. In the short term, they can help institutions to offer live, uninterrupted support. And in the long term, they can help us hone students’ soft skills, which are notoriously hard to teach and assess through traditional methods, by providing repeated, interactive practice with feedback loops that build competence and confidence.

Omar Merlo is academic director of MSc Strategic Marketing and Nai Li is head of research and impact, both at Imperial Business School.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment