Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has exposed something higher education has obscured for decades: our obsession with the final product. A polished essay – our supposed gold standard – can now be generated in seconds by a system that has never read the assigned texts, wrestled with uncertainty or learned anything at all.

If a large language model can produce a “good” text on demand, then perhaps producing good papers was never the intellectual accomplishment we claimed it was. GenAI has revealed a deeper issue: we have confused form with content, polish with understanding, and product with learning.

We could dig in our heels and double down on surveillance of our students. Or we could accept this moment as the overdue correction it is and redesign assessment around what matters: the process by which humans think, revise and learn.

- ‘Don’t be sorry, just declare it’: safeguarding the integrity of the essay

- Turn AI from a magic box into a tool to be interrogated

- When we encourage AI use, how can we still assess student thinking?

Design disciplines already do this. The critique session – not the final board – is where learning and assessment happen. Iterations, collapsed models, abandoned ideas, messy rebuilds…This is the intellectual terrain where understanding forms. The final artefact is, of course, evidence (and something that should be celebrated), but it is never the whole story.

Higher education assessment, unfortunately, is built in the opposite direction.

So, let me be explicit on what I think we should do in higher education:

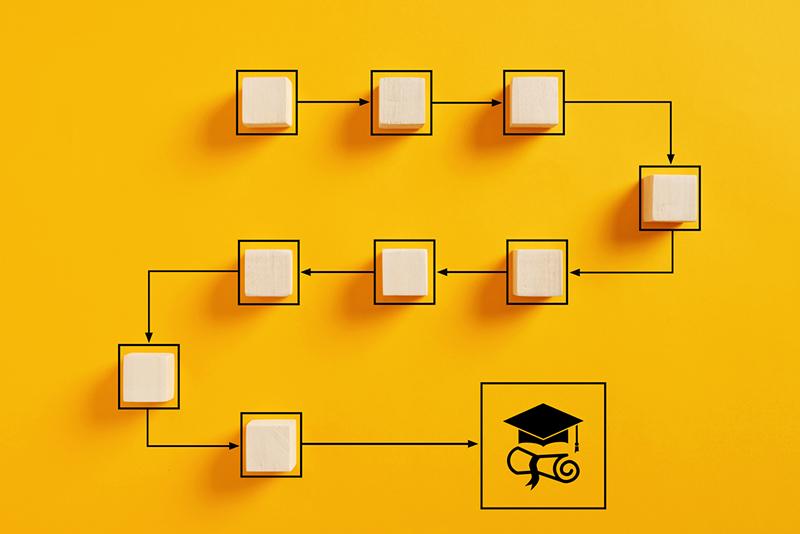

- assess the trajectory, not the artefact

- assess the revision, not the submission

- assess the quality of thinking, not the polish of the output.

Three steps towards mature, learning-centred assessment

Here are recommendations for how assessment can evolve into a more mature, learning-centred practice.

1. Make iterative work mandatory – and grade the evolution

As educators, we need to value iterative work. Stop treating drafts as symbolic paperwork. Ask students for multiple iterations towards a final output and reward conceptual movement through:

- reframing (how students redefine the problem or shift their angle of enquiry)

- students’ response to critique

- refinement and justification.

Students can, of course, fabricate drafts with GenAI – but only when such “drafts” are not connected to the work at hand. The illusion collapses when critique conversations, in-class checkpoints, personalised feedback rounds or short oral explanations accompany drafts. AI-generated work breaks the moment it must link decisions across time.

When teachers follow student thinking over weeks, the developmental arc becomes unmistakable. Under these conditions, GenAI cannot impersonate learning.

2. Use critique sessions the way design studios do

Most student seminars are ceremonial progress checks. Students present slides, faculty nod and everyone knows the real judgement will come later – on the final submission. But when that can be produced with a click of a button, where does that leave this process?

These events rarely influence grades, demand revision or make reasoning visible. Disciplines often claim they already engage in this kind of iterative pedagogy. The standard examples are “mid-term seminars”, “progress presentations” or the occasional formative check-in. The rhetoric around these practices is earnest, but the lived reality is usually far thinner. It is polite academic theatre. The process becomes optional decoration; the product remains the currency. And no number of polite mid-term rituals can compensate for the fact that the entire evaluation hinges on an artefact that can be produced without learning.

If we want critique sessions to matter, they must become spaces where works-in-progress are interrogated, failures examined and next steps articulated. When critique counts, students take it seriously.

A process-and-reflection brief with every major assignment can anchor this – students need to show:

- what changed and why

- what was abandoned

- how feedback was used

- what the student understands now.

This is evidence of learning.

3. Grade the journey first, the product second

A simple shift transforms assessment from output to process. A marking breakdown might be:

- 50–70 per cent: process, iteration, reflection

- 30–50 per cent: final artefact.

These can be tied together; the final artefact cannot be submitted without documented process.

This means that a flawless final model without a tracking record or portfolio is an automatic fail. In this model, the documented journey – not the polished endpoint – carries real grading weight. Students only reveal their real thinking when imperfection is allowed.

Of course, we do not want to romanticise sloppiness. Rather, it is the recognition that learning is nonlinear, layered and full of friction. Our classrooms should acknowledge that reality.

As an educator, practise what you teach and normalise learning processes. Show your own failed drafts. Reward conceptual risks. Highlight productive failures.

A note on educators’ workload

Educators will (understandably) argue that this approach increases workload. On paper, “more drafts” and “more critique” sound like “more marking”. In practice, it redistributes effort and often reduces the heavy, lonely marking sessions at the end of term. Short in-class checkpoints, brief oral explanations and structured peer critiques replace some of the time spent deciphering polished-but-empty final submissions or investigating suspected misconduct. When the developmental arc is visible, final grading becomes faster, clearer and more meaningful because you already know how the work came to be.

The question is not: how can we afford to do this? The more honest question is: how can we afford to keep assessing only the final product, which reveals less learning?

Education has never been a factory for perfect outputs. Students learn through layers, drafts, revisions and restarts. GenAI has simply stripped away our illusion that a perfectly worded essay can stand in for that entire process. If we value learning, assessment needs to grow up. It needs to move beyond judging the last, polished artefact and start attending to the visible development of thinking over time.

The final paper is not the peak. It is only the last step of a long, messy, human journey. And that is the learning we need to evaluate.

Pontus Wärnestål is a deputy professor in the School of Information Technology at Halmstad University, Sweden.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment