What do Charles Darwin’s seminal book On the Origin of Species and the classic Hollywood film Raiders of the Lost Ark have in common?

Instinctively, you might think not much – beyond the fact that both tell a story that is driven by a need to uncover fundamental truths. But perhaps they share more than is initially apparent. And so each offers powerful insights for researchers into how to win a wider audience for your work – however much it might require a bit of hard rethinking of your approach.

- Anatomy of an academic book proposal

- The craft and politics of academic writing in the AI universe

- Time to write is a necessity, not a nice-to-have

Stories are understood and spread far more than mere facts. For example, University of Pennsylvania researchers Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman found that emotionally resonant and story-driven pieces were significantly more likely to go viral than purely informational ones when they analysed thousands of New York Times articles in 2012.

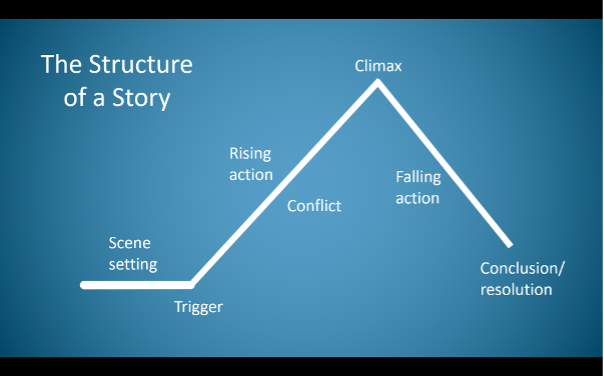

Using a classic arc to structure a story

But, you might ask, where’s the story in my research? No problem. The classic storytelling structure can help uncover a compelling narrative.

Here’s your compare and contrast to show the structure at work, with Darwin versus Indiana Jones director Steven Spielberg as your guides:

Scene setting

Darwin: Writes his observations aboard the HMS Beagle; puzzles about species distribution

Spielberg: Gives his audience a jungle temple in 1936; Indiana Jones (known as Indy) introduced through action

Trigger for the story

Darwin: Insight into natural selection as a mechanism for evolution

Spielberg: Nazis seek the Ark; Indy is recruited to find it first

Rising action that illustrates their quest

Darwin: Gathering evidence: breeding, fossils, geography

Spielberg: Indy travels to Nepal and Egypt; faces traps, rivals and ancient puzzles

Conflict

Darwin: Challenges to the theory: missing fossils, complexity of organs, instincts

Spielberg: Nazis, Belloq, betrayal, supernatural forces

Climax

Darwin: Full articulation of natural selection as a unifying theory

Spielberg: Nazis open the Ark; divine wrath unleashed

Resolution of the story

Darwin: Philosophical reflection on the grandeur of life evolving through natural laws

Spielberg: Indy survives, but the Ark is hidden away by the government

Mapping your research to the classic story structure

A classic research pathway so often easily maps on to the storytelling structure. Make it clear from the start you’re going to tell a story, and hook the audience from the off. This is an age of little time and short attention spans. If you don’t grab a reader from the beginning, you risk not grabbing them at all, as they scroll on to the next story.

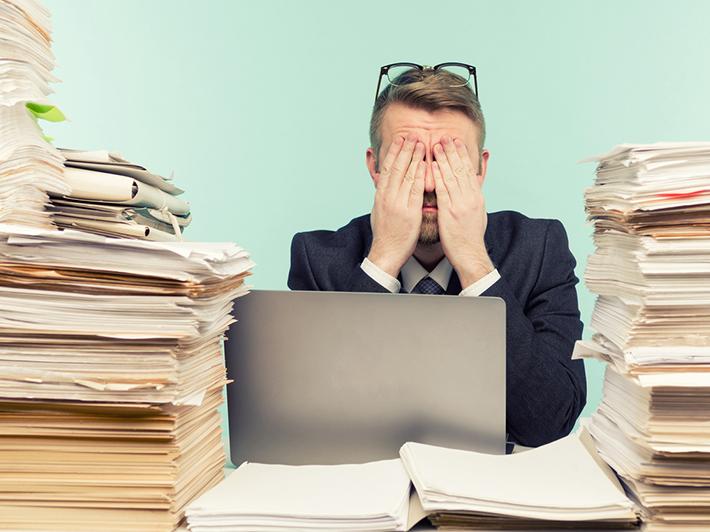

After you set the scene, the problem that’s identified is the trigger. The quest involves reviewing the literature and designing the methodology. Then comes the conflict in collecting the data, refining your approach to deal with problems, not to mention the challenge of analysing and interpreting your findings. The climax and resolution come from drawing conclusions and making recommendations.

The writing itself can help make your story “sticky”. Keep your language straightforward and simple; use plain English. General audiences can be put off by academic prose. So, don’t use scholarly terms unless you have to, and if you must, explain them in clear words and sentences.

For a lesson in how all that comes together, look at the great mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing. His 1950 paper “Computing machinery and intelligence” opens with the now-famous question: “I propose to consider the question, ‘Can machines think?’”

Both Darwin and Spielberg draw you straight into their subject, make clear we’re going to hear a story, and one that will be told in a way that is accessible for all. Turing, incidentally, shows us the storytelling approach goes just as much for the sciences as it does for the arts, humanities and social sciences, where it might seem more obvious.

Now try mapping that structure on to your research.

Turning a lesson in public speaking into a story

Here’s an example with work I’m carrying out on public speaking. I spotted a fail that I suspected would be common, and wanted to investigate that theory:

- Hook Many presentations lose an audience from the speaker’s opening words.

- Scene set I noticed repeated fails with the starts of talks from my teaching and coaching.

- Trigger One presenter had a great story to tell, but the audience tuned out and missed it.

- Quest Watching more than 100 presentations, from set-piece speeches to pitches for investment, as well as team talks by managers and lectures.

- Conflict Trying to persuade the speakers of their errors is not comfortable or easy.

- Climax Breaking through to some speakers, persuading them to try a different way.

- Resolution The presenters seeing much better results, such as winning investment for their business idea.

Thinking of your work as a story may feel strange. But give it a try. As Charles Darwin and Indiana Jones showed us, the results can be impressive.

Simon Hall is course leader of Compelling Communication Skills at the University of Cambridge Online. He is the author of Compelling Communication (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment