To prepare business students for the workplace, I encourage them to use GenAI for their written assignments. Across recent modules I have observed a consistent pattern: roughly 10 per cent of students stand out for demonstrating that they still do most of the thinking, integrating evidence from within academic articles into their work, and reflecting critically on these as well as their own AI use (as prompted by the assignment brief).

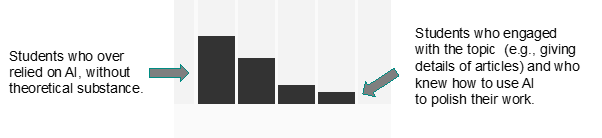

Their essays demonstrate rigour, originality and strong engagement with academic debate. On the other end of the spectrum, about half of the students appear to use AI primarily to save time. They rely on tools to generate the actual text but rarely use the gained extra time to read journal articles or refine their ideas. The result is often fluent, but shallow. The new “standard distribution” of assessment results now seems less like a bell curve and more like a set of steps (see Figure 1).

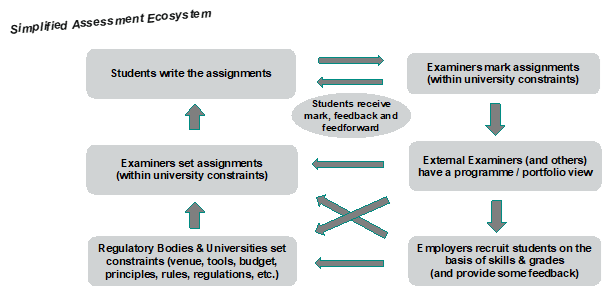

Assessors work in a complex ecosystem where they operate within externally imposed constraints (see Figure 2). Working within these constraints, I believe that setting assignments without the use of AI does not work as we cannot consistently flag the use of AI. Setting assignments that build on recalling information is equally ineffective as it can be easily done by AI. Below are some suggestions for business-school essay-type assessments that allowed me to set assignments where students could still learn by doing much of the thinking and where I could assess the quality of students’ work.

- Keep calm and carry on: ChatGPT doesn’t change a thing for academic integrity

- So, you want to use ChatGPT in the classroom this semester?

- Collection: AI transformers like ChatGPT are here, so what next?

First of all, considering that detecting hallucinations only works when we know the topic very well, I moved away from offering student-devised assessments to topics where I know the related literature very well. There is still some optionality – eg, choosing a company of their choice – but the overarching topic (in my case, for example, harnessing paradoxical tensions when using design thinking for digital Innovation) is given. Knowing the literature in depth allows me to notice when students apply and reflect on specific aspects rather than superficially dealing with them. This in turn allows me to mark students’ work consistently.

Second, I restructured a previous 2,500-word essay to a three-part assessment:

1. The main part is now solely 1,500 words and is framed as scholarly recommendation/board paper (“Underpinned by theory X, make a recommendation for company Z or a company of your choice”). The “scholarly” aspect represents the need to apply and build on academic literature in an area that I know very well.

2. The scholarly recommendation needs to be underpinned by tailored visualisations (eg, graphs, tables, images). This counts for the equivalent of 500 words and is assessed as part of an analysis rubric. Of course, students can use AI to generate tailored visualisations, however, this requires another skill set to do more than just write, and actually makes my marking more interesting.

3. The third part of the assessment is a 500-word reflection on the student’s use of AI to write the scholarly recommendation. These 500 words should be written as a scholarly blog – ie, a blog that students could post on LinkedIn (although this is not obligatory) after the submission of the assignment on the topic: “Reflecting on my use of AI for a recent university assignment”. This again needs to be robustly underpinned by academic literature, and aims to encourage a mindful use of AI while teaching yet another type of AI-augmented writing that might be useful for the students’ future employment.

The majority of students find the assignments I set interesting and thought-provoking. They appreciate that I allocate class time to guide them on how to deal with each aspect of the assignment alongside providing a detailed outline and clear marking criteria. And as the assessor, I enjoy reading the assignment outputs more than I did pre-GenAI. Writing detailed feedback, on the other hand, is perhaps now more strenuous considering that it could be streamlined with the use of AI by the assessors, an area that I believe the sector should focus on next.

Isabel Fischer is an associate professor (reader) of digital innovation at Warwick Business School.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment1

(No subject)